It is difficult enough to identify a national character within a body of that nation’s artistic product, but films embody an altogether more complicated dimension to the concept of locating a national identity. Largely, the vast diversity of films produced within a country with a healthy cinematic economy obfuscates attempts to extrapolate universal themes and motifs. More difficultly, though, the sheer expense of film production frequently requires filmmakers to seek financial support from outside their milieu. The result is a phenomenon of cross-cultural product that, by virtue of locations, talent, content, and production history, cannot be situated within the specific confines of a single national identity. The final installation in George Miller’s Australian “Mad Max” saga, Beyond Thunderdome, is intricate in such a way. According to the Internet Movie Database, Beyond Thunderdome is the only film of the trilogy (following Mad Max and The Road Warrior) whose production, not just distribution, was co-financed with foreign money from the United States. The financial interest of Hollywood suggests that certain formal and textual considerations be met in order to secure a return in its investment. This focus on commercial demands generally restricts the possibilities of a specifically Australian vision. However, with Beyond Thunderdome, directors Miller and George Ogilvie and screenwriter Terry Hayes (who co-wrote the film with Miller) manage to create a film that is simultaneously Australian in character as well as Hollywood in convention.

Frequently when filmmakers looking to export their product, rather than stripping their films of cultural-specific references, they will, instead, attempt to package their culture, hoping to appeal to foreign audiences’ sense of exoticism. It is important to keep in mind the difference between cinematic tourism and national character. While films that feature specifically Australian elements, such as aboriginal culture or Australian history, films like Crocodile Dundee or The Last Wave, can be easily identified as Australian pictures, this does not necessarily speak for the films’ identification as works with national character. This would be tantamount to suggesting that films identifiable with the kitschy term “Americana” (such as Forrest Gump and Yankee Doodle Dandy) are descriptive of the national character of the United States. A similar difficulty occurs when considering films free of specific cultural reference points: how can we identify films like the “Mad Max” trilogy, specifically Beyond Thunderdome, as Australian films when they are practically without any specific Australian references?

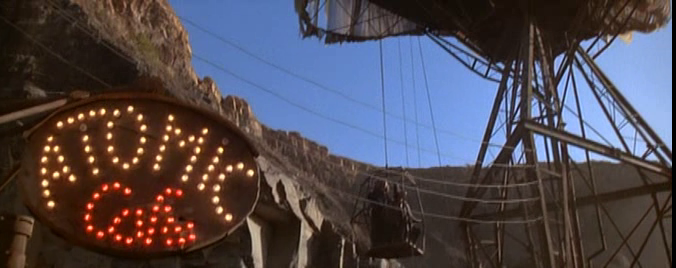

It’s immediately obvious while watching the “Mad Max” films that Beyond Thunderdome is the most well financed and globally concerned. Its budget shows in every frame, in every extravagant set, and in every exotic and attractive setting. The first two films feature scores by Australian composer Brian May. Beyond Thunderdome’s score is by Frenchman Maurice Jarre, a seasoned practitioner of bombastic, big-budget Hollywood soundtracks. Its plot is bifurcated to include intense Thunderdome-centered action as well as a more sensitive plot involving Max helping a tribe of lost children find their way back to a home they call “Tomorrow-morrow-land.” This exemplifies the Hollywood trend of broad appeal and constant narrative motion, whereas the earlier two films’ stories are more singular and contemplatively paced. There is also the inclusion of Tina Turner, whose casting as the mayor of Bartertown was one of the film’s key marketing focuses, as her Private Dancer album the previous year had gone triple platinum. With her presence also came two songs that bookend the film, “We Don’t Need Another Hero (Thunderdome)” and “One of the Living,” the former of which went on to be a worldwide hit. With her and newly-minted international star Gibson heading the cast, combined with the large-scale narrative and the opulence of its sets and costumes, it is simple to see the picture’s Hollywood influences.

However, despite Warner Brothers’ influence on the film’s production, Beyond Thunderdome still retains an identity that is markedly Australian. It is the third part of a series where the first two films were created entirely within the confines of Australian industry (picked up by overseas companies for distribution post-production). Its cast and crew are largely Australian, with a few notable exceptions including Turner and Angelo Rossitto (who plays the Master half of Master Blaster). Most important, though, are the stylistic and thematic similarities it shares with Australian films of the time. If identifying a national character is even a possibility, Jonathan Rayner suggests that three elements, chronology, style, and theme “are important in the interpretation of national filmmaking, not simply as consistencies which underpin generalizations but as continuities in communication between the subject(s) and object(s) of cultural representation.”

Stylistically, with its canted angles, quick editing, and versatile camera, Beyond Thunderdome more clearly resembles any number of Australian films (such as the films of Brian Trenchard-Smith and Richard Franklin) than it does any of the more aesthetically conservative Hollywood action films of the time (such as the films of James Cameron and Walter Hill). Just as the post-Vietnam era of American cinema ushered in a wave of lone gun action films in the Rambo vein, Australia produced a rash of B-movies in the late 70s and early 80s, sometimes centered on excursions in the desolate outback, often emphasizing vehicular travel. Kieran Tranter observes that the car is “intimately associated with Australian governance” and that the car “structures and rationalizes how Australians are known.” Seen against films like Razorback (1984), about a murderous feral boar, and The Long Weekend (1978), about a struggling couple in the middle of nowhere, a trend of reliance on cars as well as the apathetic cruelty of nature emerges. Beyond Thunderdome also exhibits these thematic traits. When Max is sentenced to the Gulag, what follows is an extended sequence of wandering anguish through the Australian desert. The horse that he is riding falls over dead then is violently sucked underneath the sand. Even after his pet monkey shows up with some water, it only prolongs his suffering the hot sun and sandstorms of the mindless expanse.

Illustrating the divide between the Australian notion of a brutal natural world and the more Hollywood ideal of an optimistic harmony with nature are the film’s two central stories and locations: Bartertown and the village of Lost Children. The depictions of both societies in the film are that of societies regressed to a “natural” state, although their philosophies about this naturalism differ. The people of Bartertown live by random chance, with no room for compassion. The Thunderdome exemplifies the Darwinian “survival of the fittest” code. Compassion is ideological, and ideologies don’t occur naturally. Whereas in the Lost Children’s village, they practice a productive relationship with nature, making clothing out of natural objects rather than junk and refuse, the way the people of Bartertown do. Not unlike the conflict between the pirates and the Lost Boys in J.M. Barrie’s story of Peter Pan, Miller and company use that basic conflict as a template to dramatize the tensions between nature and civilization, innocence and brutality, a peaceful history and a future of war.

It is useful to note the film’s heavy reliance on aboriginal culture and its popular filmic representation. From an American perspective, many of the accusations of esoterica or exoticism are rooted in the film’s aboriginal slant. The film opens with an expansive traveling aerial shot of a seemingly endless desert. After a few moments, as the camera moves closer to the ground, the viewer begins to see the shape of a caravan. Then, as the camera gets even nearer the object, a didgeridoo begins to play on the soundtrack, punctuating the emptiness and wildness of the image with an unmistakably aboriginal sound. That it is the first sight and sound of the picture (save the Turner-scored opening credits) impresses a specifically Australian cloud on the rest of the film. A few moments later, after Max has been knocked off the cart by Jedediah the Pilot’s airplane (whose point of view it is in the opening shot) and his caravan stolen, there is a series of shots featuring Max against a sky at the break of twilight, also accompanied by the didgeridoo. This image of a solitary figure in the wild is a trope of Australian cinematic aboriginal representation (as seen in films like The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith and Walkabout). This focus on aboriginal representation is highlighted by the Lost Children sequences. During the scene where the Children explain their history to Max, the storyteller holds up a frame made of sticks so that their audience views her within the frame. This apparatus ostensibly resembles a movie or television screen, with the Children (and Max) witnessing a primitive form of cinema. Although there are no aboriginal actors within the film, Miller and company are likening aboriginal Dreamtime with cinematic storytelling.

What occurs, then, is a coalescence of cultures. In native terms, the aboriginal culture, here represented by the Lost Children, melds with a post-technological culture through its use of a cinema screen proxy. This highlights the conventions of aboriginal representation, which ultimately, in conjunction with the film’s heightened style and bleak disposition, works towards the marriage of Hollywood and Australian cinematic traditions. On the one hand, it clearly demonstrates Australian attributes with its emphasis on the hazards of the natural world, its focus on cars and demolition, and its heavy reliance on aboriginal representation. On the Hollywood hand, you have a bombastic score, flashy production values, and Tina Turner. To say the film is one or the other denies the possibility that a film can belong to two cultures simultaneously. Beyond Thunderdome understands this phenomenon: in its final sequence, Max leads the Children into a sandstorm-beaten post-nuclear Sydney, whose famous opera house is the only diagetic indication of the film’s location. This last minute revelation squarely fixes the film with an Australian character. However, where this despairing vision would befit a film like The Road Warrior, where in the end Max is manipulated by the village of survivors and left on his own, the emphasis on the hope conveyed by the Children at having at last found a semblance of their history is much more characteristic of a happy Hollywood ending. The film exists as a Hollywood product as well as a fair representation of Australian character.

Affiliate Marketing is a performance based sales technique used by companies to expand their reach into the internet at low costs. This commission based program allows affiliate marketers to place ads on their websites or other advertising efforts such as email distribution in exchange for payment of a small commission when a sale results.

ReplyDeletewww.onlineuniversalwork.com